My informal presentation to ISA-Northeast 2022 on pedagogy

Apocrypha Against Canon: Breaking Free of 1648 and All That in the IR and Foreign Policy Classroom

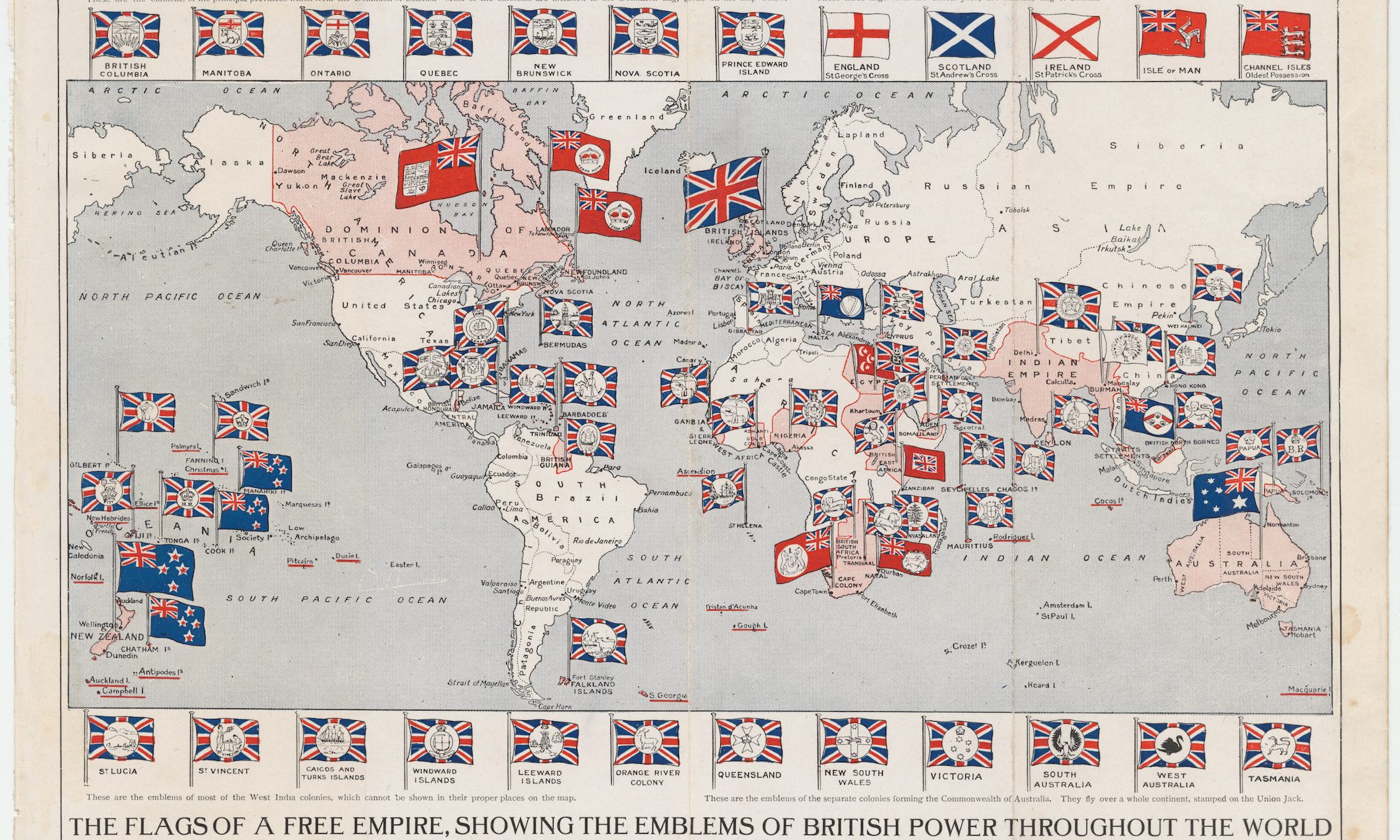

Abstract: Although International Relations is arguably becoming more diverse and less Eurocentric, the canonical timeline of pivotal events and important years remains: 1648, 1789, 1945, and so on. Even attempts to dethrone the timeline’s reign only reinforce its status as the default. To the extent that this dominance reinforces a potted historical understanding, it perpetuates a model of thinking about IR that continues to place Western Europe and its offshoots in the most flattering light at the center of world politics, rather than introducing students to the broad sweep of contestation and variation present in International Relations. One way to address this issue is to use what I term “apocryphal history”: cases that put the canonical timeline into a different light, either by showing “sidelights” of the main events, using cases other than the canonical ones to illustrate core phenomena, and by displaying fuller context of events. From using the U.S.-Mexican War to illustrate bargaining theory to discussing the cooperative roads half-taken at the end of the Cold War, this paper discusses how to reinvigorate historical examples in the classroom.

Introduction: What are we teaching when we teach “world politics”?

I teach large courses on world politics and U.S. foreign policy at a flagship public university. I like doing this, and the conditions are acceptable. Like all workers who aren’t terminally alienated from their labor, however, I want to have some meaning in what I do. Like all scholars who aren’t locked into the conventional paradigms transmitted from the past, I’m interested in finding ways to explore themes that will help illuminate students understand the world they will live in. And like everyone who fancies themself an intellectual, I’d like to put my own stamp on the material.

This leads to a dilemma of andragogy (really, we shouldn’t talk about “pedagogy” in higher ed). For all I want to shake things up and present my own arguments, we as scholars live in a society: a course called Introduction to World Politics can’t just be an Introduction to Things I, Paul Musgrave, Find Interesting. There has to be some way that my courses are inducting students into a larger field of study. And, because these are large lecture courses that form part of the (semi-)requirements of my department’s largest major and which also function as gen-ed courses, it’s really more about larger fields of study: political science, international relations, public policy, being conversant with scholarly knowledge production, and learning how to decipher articles in publications like The New Yorker and Foreign Affairs that may be foreign to my students’ experiences.

In other words, I recognize that there’s value in the conventional. I can’t just go rogue without betraying my (loose) obligations to others and my (more important) obligations to students who might reasonably assume that my courses are stepping-stones to other learning. There’s coercion, too, in the conventional. Those conventions encompass student assumptions about assessment, time to be spent on coursework, topics to be covered, and so on. It is already hard enough to dissuade students from the perception that political scientists like myself are politics super-fans or wannabe senators who have no obligations other than cheering for a team (and we all know what team they think we cheer for). Much of my classroom work is already set against this belief by proclaiming, and sometimes demonstrating, the value of theory and deep learning. That’s on top of some degree of individuation (difficult in courses whose enrollment numbers in the hundreds) and the ordinary effort involved in the maintenance of LMSs, TAs, GPAs, and other acronymical demons.

The particular set of conventions I want to discuss here, though, have more to do with the canons of what to include in a survey course. In substantive terms, those frequently include tropes like the prominence of historical markers bringing our story from the international relations of ancient Greece to the maneuverings of today’s great powers or deliberations about the Paradigms and what wisdom they have today. In formal terms (that is, literally the forms of what we convey), that often involves a reliance on textbooks, readers, and pop political science translations (that is, Monkey Cage and similar “explainer) pieces. And in disciplinary terms, it means enforcing boundaries about who counts as IR and what subjects matter.

I am not, particularly, an iconoclast. My syllabi are still pretty conventional and my courses use textbooks when good ones are available. But I have tried to strike out on my won in a couple of ways. One way, which I won’t go into here, is making sure that I have pieces that address the abstract and remote issues we discuss in our theories and cases in more humanistic ways. That includes making sure there’s some poetry or first-person essays or a short story in World Politics. Another way, which I also won’t go into here because I’m not doing a good enough job at it right now, is in trying to use examples in World Politics that, well, come from world politics–less Europe, more India; less USA, more Americas.

The way I want to talk about balancing these tensions, instead, has to do with how I try to choose cases that are before, after, or besides the conventional cases we use to illustrate key concepts–and, in one case, how I choose cases that conventional readings leave out of international relations altogether. In this way, I think of myself as trying to break out of the particularities of The Canon, or at least of the canonical cases, by using cases and topics that aren’t quite as easily available. Doing so, I think, can lead us to another way of rethinking the canon of IR: moving beyond the standard histories we know are wrong to less familiar territories that can provide useful encounters.

Making a Canon

Organized Christian and Jewish practices recognize some scriptural texts as belonging to a different status than others. For Christians, the practice of constructing a Biblical canon took, at a minimum, centuries–millennia, if we view Protestant reforms to Old Testament inclusion as a part of a process that began with the compilation of the Hebrew Bible. The process was not smooth and was not pre-ordained: Is 2 Thessalonians canonical? Well, maybe not, but probably so. The Apocalypse of Peter? Well, no, even if the contents of that apocryphal text seem pretty close to the vulgar beliefs of the demotic church.

The process of constructing a canon of international relations cases has been no less … divinely guided. Some cases (the Second World War, the First World War, the Cuban Missile Crisis) were born canonical; others (Fashoda, the Montreal Convention) have had canonicity thrust upon them. There is no one path to becoming part of the canon: objective importance or scholarly interest, for instance, can elevate a case to this point. Once chosen, the status is semi-permanent: at this point, everyone in the USA has their lecture notes on the Cuban Missile Crisis set, and no amount of change in the world (or, often, in the scholarship) is going to stop it being the focal point of a good many lectures in intro courses. The canonical cases can be short (“the Treaty of Westphalia heralded the modern states-system” is a statement nobody has ever written but which everyone will recognize and most, by now, will doubt) or they can be as lengthy as an assigned book, but they are in the main familiar to everyone who teaches the subject.

That common core of knowledge helps communicate some concepts well, not least because the cases are so well understood that they have been taught repeatedly and materials are readily available. Yet the construction of a canon has also created both non-canonical cases. The vast library of these cases include ones that are too messy, unfamiliar to students, or otherwise inaccessible for intro courses. Yet it’s likely that the set of cases that could have served as well as some of the other ones that have been elevated exceeds the number of cases that were included. And, in fact, given the (seemingly) enormous switching costs, it’s likely that there’s a lot of cases out there in the apocrypha–cases that are eligible to be included but haven’t been–that we could use to better effect.

Cases from the Apocrypha

What would those cases look like? Well, they’d explore topics and themes that are of theoretical interest and which display clear evidence of that mechanism or concept’s operation. Ideally, furthermore, they’d also stretch students just a little in terms of introducing them to something that’s superficially familiar but strange or something that’s in the “Extended Universe” of the standard K-12 American educational curriculum–something that, once you know it, makes the standard saga more comprehensible.

One of the cases I use in my U.S. foreign policy course is an excerpt from The Familiar Made Strange, an edited volume by historians, which deals with the 1965 immigration reform. Rather than slot the case into the conventional, retrospective reading of history, in which the bill opened up greater immigration to the U.S.A., Jesse Hoffnung-Garskof (a historian and specialist in Latinx studies) talks about how this outcome was inadvertent and rested in large part on the unexpected reach of the bill. Doing so allows me to talk about the continuities of today’s immigration debates with the debates that allowed many of my students’ families to come to the United States while simultaneously troubling notions of the USA as a “nation of immigrants.” (Astute readers will also note that this means my US Foreign Policy course treats immigration as a fundamental foreign policy issue, which it very much is.)

Another case I use in my World Politics course concerns U.S. territorial expansion during the 1830s and 1840s, in particular the parallel negotiations between the USA and the United Kingdom over the status of Oregon and the war with Mexico over (at least initially) the status of Texas. These are not particularly familiar cases to my (mainly Northeastern) audience. Indeed, for all the importance of the U.S. war with Mexico, it hardly registers in most K-12 curricula. A good many of my students may graduate college without otherwise hearing about this–even though it has been foundational to shaping the continent on which they live. These cases thus help me teach my students something about the processes that have concretely shaped their country and its relations with its neighbors. They also help me illustrate the bargaining model of war and different outcomes. Further, by portraying the Mexican war using a source that’s anchored in the Mexican perspective, I can talk about the domestic politics and identities involved on the Mexican side of the conflict, thus de-centering the U.S. perspective while also making clear how such processes can produce bargaining failures.

The apocryphal cases can also be useful for public-facing work and other forms of scholarship. In an article for Foreign Policy published last November, I investigated the case of one of those Internet facts that springs to life, zombie-like, every few months: the fact that Pepsi once “owned” the “fourth-largest navy in the world”. Well, in one particular sense, yes, but in any meaningful sense, no–but that case nevertheless proved an important and accessible road into thinking about the development (and eventual failure) of commercial ties as a way out of the Cold War without having the Soviet Union collapse. The piece explores the limits of commercial ties as a way to piece but also, more importantly, how difficult to predict the future is when you’re living history forward instead of recounting it backward. Even if I’m a staunch presentist (or even futurist) in my course design, I try to fight presentism in terms of the perspective we bring to the past when I’m teaching. (To be sure, other scholars have addressed these topics, and done so in more depth, although to be fair to me, not in as interesting a way and not in as short a length–assign this piece in your IPE, business and politics, or Russian foreign policy course!)

In my World Politics course, I’ve begun treating a case as central to IR that is marginal to the discipline: indigenous-settler relations. Although entire subfields of scholarship are centered on this issue, relations between settler countries and indigenous societies are not central to political science or international relations writ large. Indeed, from the habitual state-centric paradigm of many intro courses, Native politics really doesn’t exist. There is good work (and we need more) out there to be taught on this issue. In particular, intro American courses need to recognize that U.S. sovereignty is inextricably a multi-polity one, with not just states but also tribal governments existing as sovereign within the framework of the U.S. political order. (In the same way, my U.S. Foreign Policy course treats the mechanics of U.S. formal empire as part of its remit, since at a minimum imperial possessions condition U.S. interests and prove to be literal testing grounds for U.S. exercises of power, whether administrative or nuclear.) Studying indigenous politics not only entails the recognition of indigenous peoples and societies as a part of political systems. It entails discussions about what the extension of the “Westphalian state” actually meant, about the boundaries of “civilization”, and about the negotiated and unsettling ways that a good chunk of the currently sovereign countries in the world came to be. This is not the same as incorporating “race” into international relations–it is in many ways parallel, to be sure–and the topics that it raises allows for discussions of South American and antipodean politics in ways that often don’t come about.

In World Politics, we also talk about the distinctions that drive global politics. One unusual way I get at this is to teach an excerpt from Ashley Mears’s Very Important People, an ethnography of VIP rooms at exclusive clubs. It’s got everything: drugs, alcohol, the accumulation of capital, gender roles, immigration and migration politics, Bourdieu–and not much sex, because the point of being in the club is showing that you are in the club. There’s other ways to talk about how constructivism and social mechanisms influence the accumulation of certain types of capital and the dispensing of other types, but why not do it in style?

Finally, and again in World Politics, we don’t start with the Greeks. The ancient Greeks weren’t central to ancient international relations. We start with the Egyptians and the Amarna System. Others might be better placed to start with something in South Asia, in the Mayan world, or in the Warring States period, but I … happen to like the opera Akhenaten (which is not historically accurate). The Greeks can come back at some point, to be sure, but Thucydides wasn’t the start of the story–neither were the Amarna letters!–and starting off with yet another bad history of the Peloponnesian War seemed to me to be doing a disservice to everyone involved, including myself, while reinforcing some rather harmful stereotypes about the centrality of “the West” to many conversations.

The Case for the Canonical Cases

The case against doing all of this is that it might weaken my students’ ties to the rest of the discipline. It’s probably a good thing for folks studying a similar topic to have similar understandings of cases, after all. That could be the case even if the common understandings are wrong. A Schelling point isn’t the best point to meet in a city–it’s the one that you can get to with the greatest chance of seeing someone else. If our just-so stories about the Cuban Missile Crisis (or whatever) are wrong, well, at least they’re common.

Okay, that’s a strawmannirg of an argument. But it’s not entirely wrong. There really is a reason we get away with shorthands we all know are wrong, like “Westphalia” or “1918” or even “the end of the Cold War” (please give me a date). All theories are wrong, some theories are useful, etc.

Strawman or no, though, I do think that the case for the canon should be heard out. I’m just less inclined to defer to every part of it than I used to. Fortunately, at this point, there’s enough anti-paradigmatic extremism that I can avoid teaching the tedious paradigms in World Politics (or, rather, I can teach the isms that matter: racism, capitalism, imperialism…). Teaching less about cases that are overtaught in the world, like the Second World War, means I can use better cases to talk about things that take place in the world. Indeed, it often means choosing more representative cases or cases that look at more interesting topics than the rather closed-off and stale canon. Probably the most important example of this, of course, is the way that The Clash of Civilizations (in whatever form it takes) became a part of the canon. As I’ve written elsewhere, this (like the parallel canonization of eugenicist Garrett Hardin) was a mistake, and one that’s wasted a lot of time. Teach Ostrom instead of Hardin, and teach anything instead of Clash.

My point, then, is that we should realize that the canon of IR isn’t divinely inspired. The canon is what we make of it — and within a good deal of discretion, we can make of it something a lot better than we’ve been handed down.