At Foreign Policy, Stephen Walt lists the five things a B.A. graduate in International Relations will actually remember five years after graduating. I think his list is (a) right and (b) horrifying because its right, because it largely recapitulates some lessons that IR scholars confidently but wrongly impart to their undergraduates, even though we know better.

Taken together, Walt’s list is an excellent summary of the kind of international relations you should understand if you were trying to become the next Otto von Bismarck. The focus is almost entirely on great powers and their employee-officials–the admirals, generals, diplomats, and merchants who want certain things from their governments and societies. It well describes the sort of status games and international relations that defined intra-European relations between roughly 1865 and 1945.

Yet for those of us trying to understand worlds beyond that–not only the world of 2016, but how international relations functioned in East Asia or ancient Assyria–Walt’s toolkit offers almost no purchase. Are you interested in how to explain TTIP or TPP? The only thing that Walt offers to you is comparative advantage, which hardly suffices to explain why rich-world governments are trying to export protections for intellectual property. Curious about why Russian and American nuclear stockpiles have been diminishing in quantity for decades? Good luck–the only tool Walt offers is balance of threat, which cant tell you why Washington viewed Moscow as so much less of a threat in 1989 compared with 1981. And if you want to craft an effective strategy for dealing with global climate change, well, once again you only have one tool: Walt suggests that something called social construction explains why attitudes toward global warming are shifting. Of course, without a lot more work, you cant explain why those shifting attitudes are only weakly (at best) influencing global coordination on the issue, or why its proven so much harder to fix carbon emissions than CFC emissions, or why national opinion polls reveal so much variation between (say) the US and other wealthy countries. And if you think that peoples identification as members of a nation, race, or gender matters for international society, you’re similarly relegated into this vague laundry list of social construction–not the real issues of war, trade, and bureaucratic politics.

Let me be clear: my quarrel here is not with Walt. I want to be especially clear because, in scholarly terms, I am a minnow and he is a whale. Instead, my discomfort arises because I think that Walt is accurately summarizing what most IR students in undergrad will remember from their time with us as students. The fact that those lessons are either (as I explain below) wrong or insufficient to grapple with the challenges of not only the 21st century world but any era means that in many ways an undergrad who has learned these lessons well will be worse off in her ability to understand the world than someone who has learned a lot of economics, sociology, or history. The weight of my discomfort is lessened because I know that many instructors have broken away from this traditionalist paradigm. On the other hand, breaking away may be liberatory but it might also mean that a unified and coherent paradigm is being replaced by a kaleidoscopic and beautiful but ultimately fractious approach to the discipline.

So what should our students take away from four years spent majoring with us in IR, international studies, and cognate fields? Well, of course I have a list.

1. The world is not flat or anarchic: hierarchy matters

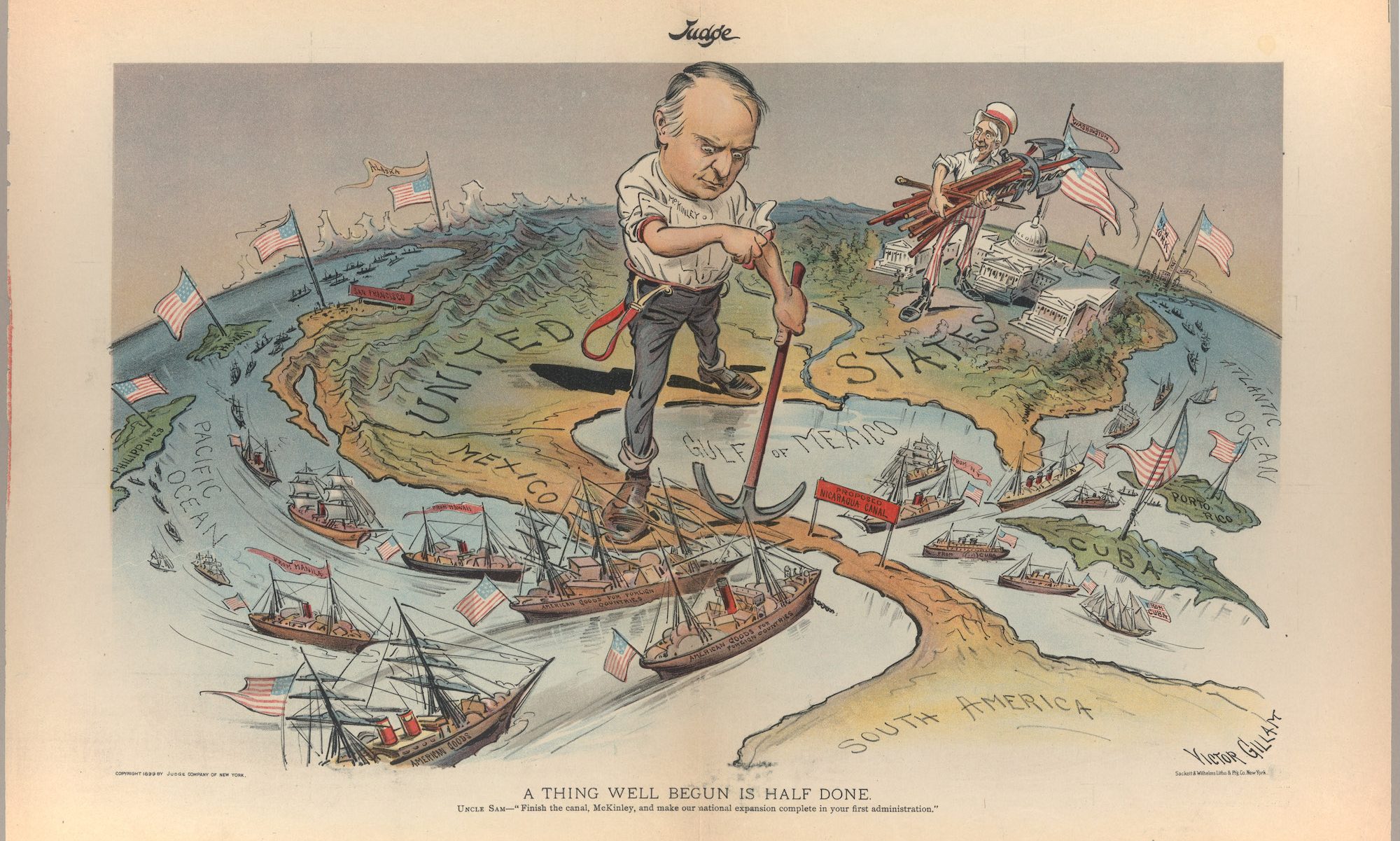

The current incarnation of IR arose after the Second World War as American policymakers and others scrambled to make sense of a world in which traditional great powers had been vanquished or were rapidly giving up their status. In consequence, the United States, which had long underperformed as a great power both in terms of providing public goods and in terms of seizing private booty, faced the choice of acting as a hegemon or of retreating to a beautiful seclusion in the Western Hemisphere. In this environment, internationalist policymakers and scholars faced a threefold challenge: to make sense of U.S. interests in a rapidly changing international society, to devise a strategy to pursue those interests, and to bring people along to supportand to run!the resulting institutions (which included not only the UN, the IMF, the World Bank, the GATT, and so on, but also the Department of Defense, CIA, USAID, etc).

Models for that kind of polity existed; they were called empires and concerts. Empires were suddenly illegitimate (indeed, the US too-rapidly disposed of its chief colonial possession, the Philippines, to make a point about the illegitimacy of empire), so whatever strategy the US pursued couldnt go by that name. Whatever emerged from the Second World War would have to be a community of (formal) equal participants. Accordingly, anything that formally signified that one state ruled over another was illegitimate. Concerts of great powers or of great and lesser powers solved the problems of respecting equality, or at least a modified version of it. In similar circumstances, an earlier American administration had signed on to British imperialists idea of a League of Nations after the First World War. Yet concerts proved unworkable because of domestic and international opposition. Domestically, a substantial bloc of Americans worried about surrendering U.S. autonomy to a supranational organization. Internationally, the idea probably would have proved unworkable, since substantial powers (especially, but not only, the USSR) proved to have insuperable obstacles toward U.S. cooperation.

With concerts and empires off the table, then, the notion of anarchy proved attractive to thinkers. In anarchy, all are formally equal (none are entitled to command, and none are required to obey). But, of course, equality by itself does not imply anarchy. In a liberal democracy (as the U.S. professed to be, despite the Apartheid nature of its Southern states), all citizens are equal, too, but some citizens are entitled to command and others required to obey. However, if all are sovereign within themselves, then there can be, by definition, no overarching power, and so no greater power could bind the United States.

Of course, anarchy was always a myth. Its altogether true that international law stipulated that Iran or Chile or Italy could choose their own form of government; in practice, however, the United States displayed no compunction about limiting, and sometimes installing, such subalterns governments. (The Soviet Union was even more intrusive within its sphere.) The world only felt anarchic in the IR sense at the very top: only American policymakers felt that there were no superior powers limiting their sphere of actions. Reading the deliberations of British or French decision-makers makes clear that the other Allies knew the ranking of power and the limits on their autonomy quite well; the Soviets were less reconciled to their role, but they also knew that their action was quite circumscribed by American power.

In place of anarchy, then, the world after 1945 was much like the world after 1991 or the world before 1945: defined by a hierarchical ranking of power that structured and ordered international policies. The forms of that hierarchy differed, of course; Harry S Truman was sufficiently modest as to not add -Emperor or Defender of the Freedoms to his titles, as earlier potentates might have done. But to characterize world politics as anarchic misses another point

2. World politics is created by people, not states

The idea of anarchy reified the kinds of distinctions that statesmen and soldiers had always sought to define between international politics (a high-status game) and domestic politics (a much grubbier affair). International relations was portrayed as a game with few players (perhaps four or five before the Second World War, two during the Cold War, one afterward) dealing with few issues (war, trade) according to a single guiding factor (the national interest). This simplification made international politics seem much more understandable, tractable, and elegant than the messy business of domestic legislating, which never seemed to end. Add to this the fact that relatively few people went into IR as a profession, and they tended to be witty and erudite folks with mastery of recondite technical vocabularies, and IR practitioners could enjoy all of the trappings of scientific and artistic mastery.

This ironclad distinction between the spare world of international relations theory and the messiness of domestic politics required sweeping under the rug literally everything else about international relations besides the high politics of the great powers. The US-centric IR schools of the high Cold War didnt much care to talk about international migration, changes in culture, the messy business of development, the ways that attitudes shaped and reflected actors status, and so on. Indeed, you have to be very well-versed in a certain form of international relations theory to ignore what people actually do in international life. But a combination of funding and first-mover prestige advantages meant that IR as a field long devalued anything that didnt look like the kinds of political moves a Bismarck, a Talleyrand, or a Pericles would have made in international contexts. Ordinary people all but disappeared from theory textbooks, except when they showed up as abstractions, as in statistical charts or calculations about the megadeaths that a nuclear exchange might lead to. The closest that they came to appearing, in fact, was when experts in psychology and foreign policy noticed that sometimes officials behaved like people and not like perfect rational actors.

It goes without saying that, in this framework, the experiences of people who lived in the countries that played the role of surrogates in great-power conflicts (the Vietnamese, the Cubans, the Angolans, the Afghans) were, at most, considered only incidentally to the high-political games of the great powers.

Focusing on world politics as a game among states, in other words, meant that the field for a long time ignored or at least substantially discounted the ways that peoplenot just presidents and premiersrelated to, participated in, and created world politics. Those were not Important.

3. Formal politics looks Important, but its only a small part of the story

Focusing on Importance leads us to ignore what really matters. The worldview Walt expresses is one in which people whose business cards have Important Titles matter more than others. If your business card identifies you as President of Fredonia or General Secretary of Arstotzka, then you Matter. That relates to the idea that theres anarchy between states and politics within states: the formal government formally rules, so it must matter, while between states theres no supervening powers, so what could matter there? Of course, that perspective ignores the fact that the international community has spent hundreds of billions trying to change many of the newest states in the international system into functioning states. The World Bank and the IMF, for instance, exist largely to create states of a certain mold where there hadnt been ones before. And in many states, the people who actually matter may not have business cards at allor their business cards may refer to positions that the rest of the world doesnt recognize officially, even though everyone knows that they matter quite a lot. (Think of Osama bin Laden or Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, or even Deng Xiaoping, who didnt have any official position after 1992.)

More to the point, anyone whos ever read a history of anything (or worked in an organization) knows that simply paying attention to formal documents and official hierarchies is almost always a perfect error. The real stuff of life happens according to informal understandings and workarounds that become, over time, part of the culture and lived experience of a world. And a lot of what matters obeys the Ferris Bueller principle: Life moves pretty fast. If you don’t stop and look around once in a while, you could miss it. Reducing international relations to war and peace, or even the somewhat broader war-and-trade paradigms, means that we assume that it doesnt matter if people in France eat McDonalds or if Chinese censors edit Hollywood scripts. And yeteppur si muove: these are precisely the sorts of things that people do seem to spend a lot of time thinking about, even more than the sorts of Important Issues that experts believe matter.

By the way, this move is a mistake even on the Important Experts own terms. Refocusing international relations to take these sorts of observations more seriously actually helps explain why the formal politics matters so much. Insisting that international politics takes place Over There, Remote From You is the worst thing that an expert can do. Abstract models of trade politics become much more interesting when you spell out what those models imply for your community. (I taught comparative advantage differently, and much worse, when I lived in Washington, D.C., than when I later lived in parts of Pennsylvania and Massachusetts that had arguably lost more than they gained from trade.)

4. The dividing line between the international and the domestic is mostly illusory

In the United States, its easybut wrong!to believe that there really is a division between domestic politics and international relations. Especially if you equate international politics with big questions of war and trade, the average American simply doesnt encounter those as part of daily life in the way that the average Chinese or Iraqi does. But any neat division between international and domestic falls apart rather quickly upon examination. As an example: try to write a history of Japanese politics after 1945 while insisting on an international-domestic division. Try to explain contemporary UK politics without using the term Europe. Investigate why Donald Trump likens the U.S. to a loser without looking at his supporters perceptions of international status. Or try to work out what Rwandas domestic spheres of governance actually are. And so on.

These thoughts are pretty much anathema to theories of world politics that prize parsimony above all else, but thats too bad for parsimony. Einsteins theory is much less parsimonious (in some ways) than Newtons. That doesnt mean that simpler theories are never useful: you can get quite good results using Newtonian mechanics. But it does mean that you need to understand when to switch from the simple to the complex.

5. International relations is a social construction

Walt and I agree on something foundational: international relations is a social construction. In one weak sense, that means that we could all change our minds and make the anarchical world system whatever we wanted to; in practice, however, we should note that most identities seem pretty sticky. But recognizing that shouldnt just be a footnote. Its the foundation of what we should be studying, and we should grapple with the implications all the time. That recognition entails understanding that human beings must be understood as social before anything else, that ideas not only matter for international politics but they constitute international politics, and that the representations of international politics precede counts of tanks, ICBMs, and GDP in analytical importance.

I will give odds that the importance of social constructivism will only accelerate as the growing enrichment of historically impoverished parts of the world enables powers that have been lower-status until recently to construct alternative logics of identification and to provide the material conditions for alternative representations of international/transnational societies to flourish. The shared basis of communication for global society since the 1750s has been deeply influenced by the particular interests, interpretations, and quirks of the English-speaking communities of the North Atlantic. That condition, however, will be temporary, in the same way that cultures that based their shared understanding of the world on ancient Egyptian or Greek ideas proved transitory. At some point (and it may be sooner than we think), the world may move from its current globalized state to one in which several smaller, more distinctive communities co-exist with deep relations among them and few relations between them. (Imagine the world ca. 1350, when Europeans, Central Asians, East Asians, and members of the Islamic world knew of each other, traded with each other, and studied each other to some degree, but viewed themselves as living in different spheresand didnt even know about the worlds of the Americas.) At that point, the simplified rules of international relations that served the needs of American policymakers and students well in 1945 will be put aside as the local approximations they always were.