Attention conservation notice: Doug Mack has written a good, short, breezy book about the territorial possessions of the United States, a topic that should help to shake conventional ideas of what the “United States” is.

Attention conservation notice: Doug Mack has written a good, short, breezy book about the territorial possessions of the United States, a topic that should help to shake conventional ideas of what the “United States” is.One of the great thrills of social science should be the constant rediscovery of the world as begging for explanation. Viewing social life as a dynamic process should prompt a constant unsettling with the superficially —a disenchantment with received wisdom and estrangement from the familiar. When we flatter ourselves, social scientists preen themselves on exactly those dimensions: interrogating this and wrestling with that.

Of course, social life being infinite, most of the time we fail at this task. Intellectual fashions provide the most obvious evidence that much of what seems to be deep engagement really arises from fads. More fundamentally, however, researchers often proceed from “stylized facts” about parts of the social world that are merely better drawn caricatures of social life than the non-specialist presents. Even if we manage to liberate ourselves from the tyranny of conventional wisdom in some particular niche, the necessity of producing a steady stream of work that engages our fellows and our blind spots about our own ignorance (compounded by the epistemic arrogance that a professional standing as an “expert” breeds).

I am at least as guilty of these tendencies as the next social scientist. There is one small region in which I am slightly less guilty than my fellows, however: I think — I hope — that I take the peculiar composite nature of the United States government a little more seriously than the average scholar of international relations. For me, the “United States” is never a unitary actor, even if its outward appearance sometimes puts such a mask over its structurally divided government. Instead, I view the country as a patchwork actor, one marked by multiple traditions of identities, governed by two major parties who alternate according to a coin flip, and divided into fifty states and territories.

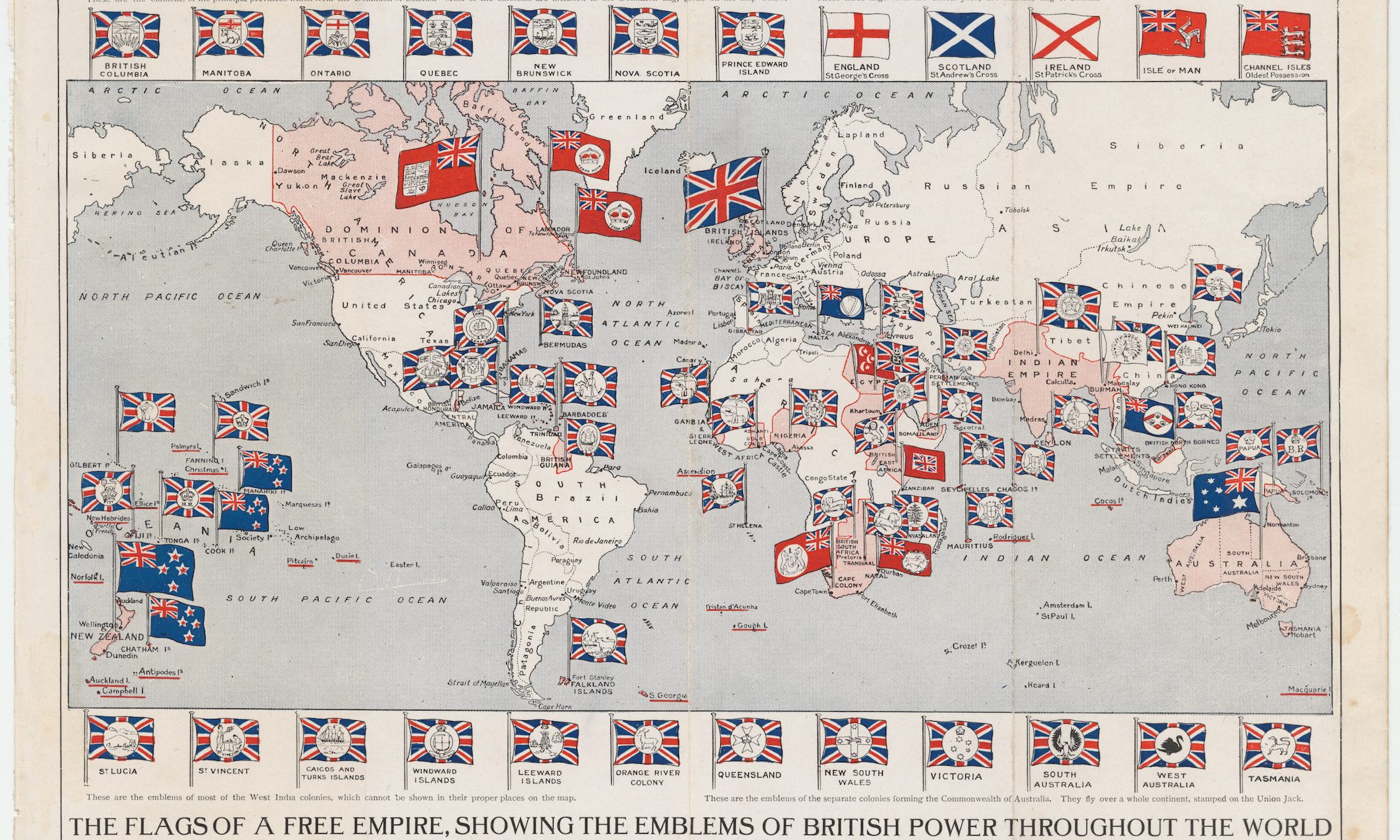

It’s the “and territories” that, as Doug Mack describes in his new book The Not-Quite States of America, people often forget. A chance encounter with ceremonial quarters honoring Puerto Rico, Guam, US Virgin Islands, American Samoa, and the Northern Mariana Islands jolts Mack into realizing that millions of people—many, although not all, American citizens—live in what can only be described as a U.S. empire. Unsettled by this estrangement from the familiar, he sets out to visit them to learn about their people and their culture to make them more comprehensible. Mack’s book is a sugar-coated challenge to the way you will think about the everyday politics of “America”– and a surprisingly sharp (if inadvertent) challenge to categories IR and comparative scholars employ to divide the world.

Continue reading “The Not-Quite States of America, Doug Mack [Review]”

For reasons involving real research, I need to see whether and how much the Iraq war affected the Bush administration’s electoral record. I’m reviewing some of the literature here, partly as a public accountability mechanism, partly as a personal note, and partly to see if anyone else has anything to add.

For reasons involving real research, I need to see whether and how much the Iraq war affected the Bush administration’s electoral record. I’m reviewing some of the literature here, partly as a public accountability mechanism, partly as a personal note, and partly to see if anyone else has anything to add.

Originally written for

Originally written for