Every chapter of Michael Lewis’s The Sixth Risk, as it sounds to somebody who had heard of the federal government before November 2016.

John “Curley” Stooge was an unprepossessing man–White, middle-aged, and graying at the edges. As I nibbled on a pastry in the kitchen of his modest 3,000-square foot McMansion, I listened to him tell his totally relatable story. “As a freshman at MIT, I’d wanted to do something normal, like become a nuclear engineer,” Stooge said. “Then, out of the blue, I was picked to become an astronaut. It was a change from what I’d wanted to do, but I thought it could still be a challenge.”

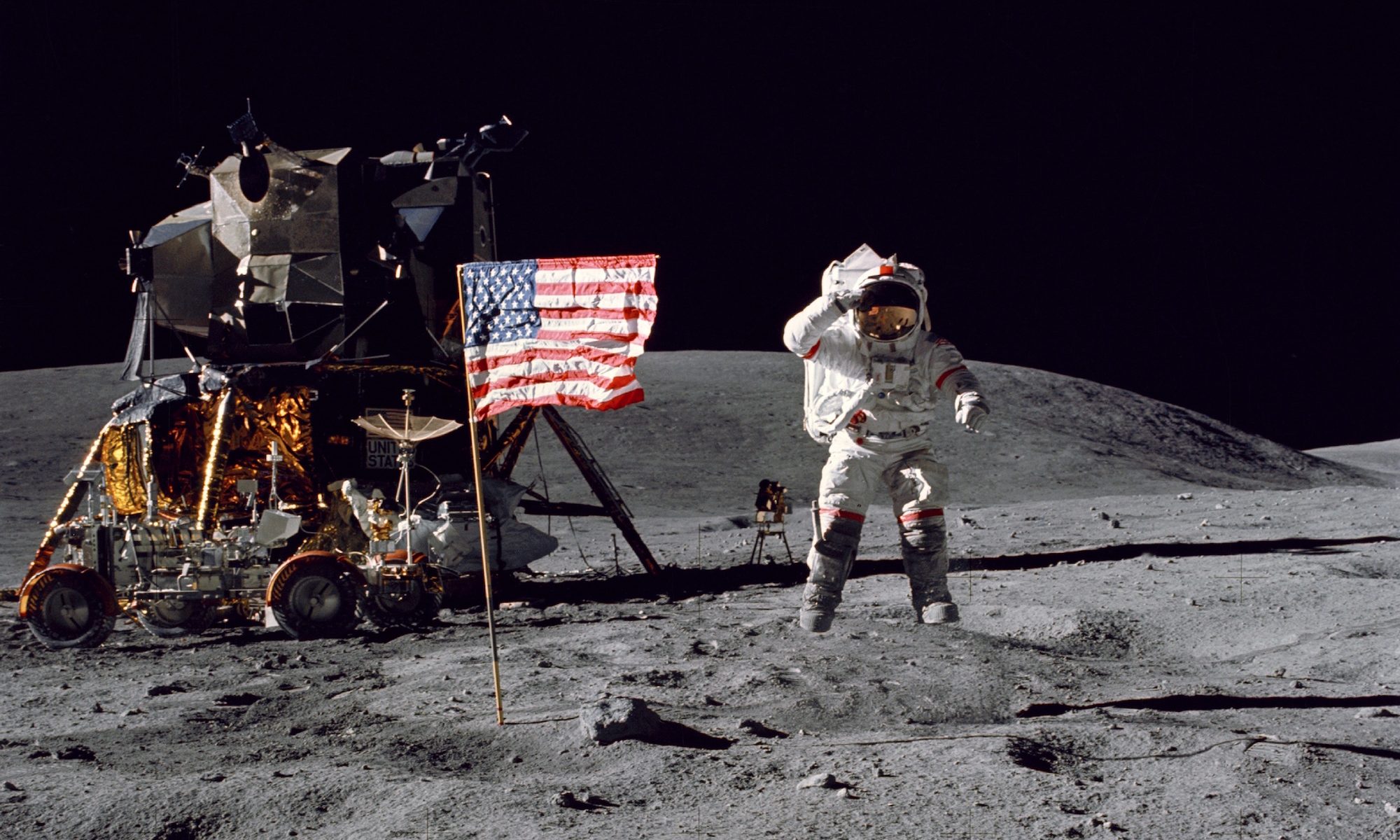

It would be a challenge. An “astronaut” is a federal employee who travels to space on behalf of an obscure agency called the “National Aeronautics and Space Administration.” If you’ve never heard of it, it might surprise you to learn that NASA has run many complex projects, including Skylab and even once putting men on the Moon. They even returned them safely to Earth! Of course, NASA has had some problems, like when they commissioned the most dangerous passenger vehicle ever launched, but that was because of Republican dreams of privatizing space. Besides that, however, the space agency’s record of manned space flight has been meaningful and successful in vague ways that cannot be quantified.

“After being an astronaut, I decided to give back to the country,” Stooge said. He spent a few years in the private sector making an absolute metric ton of money–literally: he ran a gold mine in South Africa and was paid in bullion–before being named Assistant Deputy Secretary of Defense in Charge of Space Warfare. “It came as a total surprise,” Stooge reflected. “I’d only given the Obama campaign several hundred thousand dollars and written three New York Times columns praising his plan to give SpaceX control of Mons Olympus, so when the call came I was politely shocked.”

In his new post, Stooge learned a real appreciation for the ways of government. “I didn’t know much about the civilian side of the defense side of the government,” Stooge said. “But the people there were really smarter than I’d expected. It turns out that even non-astronauts with fewer than two Ph.D.s can breathe through their nostrils, mostly.”

Stooge oversaw large and obscure projects of the federal governments, like the launching of “artificial satellites” that contributed to a “global positioning system”. Not many people have heard of GPS, but it’s used to tell Google Maps how to get to your nearest Williams-Sonoma or Crate and Barrel. It’s just one of the ways that Pentagon spending affects our daily lives–yet another reason why literally any deviation from the status quo must be resisted.

“I really enjoyed the work,” Stooge said. But everything changed on Election Day 2016. “We’d never thought that anyone but a perfectly liberal technocrat could win an election in a democracy,” Stooge said. He and his staff continued work on the Tantalus Kill-a-Tron 3000, a project that would give the American president the power to kill anyone anywhere instantly by the press of a button or a typo. “This was important work,” Stooge explained. “We’d wondered at drinks after late nights perfecting the Kill-a-Tron if it could ever be misused, but who ever thought that power might lead to corruption?”

The incoming Trump administration took weeks to learn basic facts about the Defense Department, like the fact that the “Pentagon” is a five-sided building that houses its leadership or that there were different parts of the military. “The ‘landing team’ was just six guys, all named ‘Chip’ and all from Jared’s real-estate firm,” Stooge recalled. “They showed up to be briefed, but ten minutes in they were asking questions like ‘wait, we don’t have a Space Force?’ and ‘so are we winning this war in Afghanistan or not?'”

Now an unemployed former official who works part-time as a vice president of Lockheed Martin, Stooge has adjusted to losing his government salary. But he worries about the Trump administration. What’s the biggest risk of the Trump administration, I ask him. He looks at me as if I’m slow. “The fact that the president can launch a nuclear war at any time for any reason,” he replies, slowly.

He can? I ask.

“Yes.”

I didn’t know that.

“You also didn’t know what GPS was,” he replies.

Okay, point taken. Before November 2016, I’d never really thought about the federal government, but over the course of reporting this book I’d come to learn that all those people in government buildings did things, all the time, mostly, and that at least a half-dozen of them were important. It stood to reason that the president and Department of Defense also mattered.

For some reason, I had earlier decided that I would just ask questions of former officials in this manner, often going on for pages and pages, just recapitulating things that should have been obvious to anyone who’d heard of “food stamps” or “the National Weather Service.”So what’s the second-most worrisome thing about the Trump administration? I asked.

“Definitely the Kill-a-Tron 3000.”

Yeah, that sounded pretty worrisome to me, too. If only someone had been paying attention before giving the government to a failed New York real-estate buffoon, we might have had a discussion about the wisdom of building such a project. But it was too late for recriminations. I had to leave for drinks with someone who had once worked at a little-known government body called the “Federal Reserve.”